This summer, Max and I took our very first trip to Glacier NP. Aside from seeing the park and playing tourists, our goal was to join Eric Hardwick and his team on their yearly pilgrimage to open up new canyons in Montana. Eric is the creator of the Canyoning the 406 website, devoted to posting beta for Montana canyons. Due to the short season and the dearth of Montana canyoneers, Glacier canyons are currently largely unexplored.

At the beginning of August, we took the trailer and drove 10 hours from Washington to Glacier to meet up with Eric and the rest of the crew. Just as our luck would have it, the weather that week was unusually wet and stormy. Evidence of past fires was abundant in the park, but we experienced thunderstorms almost every night, forcing us to recalibrate our plans daily. It was after getting an inch of rain overnight that we decided to explore Siyeh Creek as it wasn’t extremely narrow and was still relatively safe in higher flows.

Siyeh Creek, like some of the creeks in the park, is accessible via established park trails with the main obstacle being very limited parking. Most of our days started extremely early so we could find parking before the tourist hordes arrived. So it was on a particularly cold and wet morning, our group found ourselves in the Siyeh Creek parking lot, getting ready to hike with many millimeters of soggy neoprene, ropes, a drill and bolting materials.

The goal of our expedition was to explore the technical section of Siyeh Creek and establish a route by creating either natural anchors off trees and logs, or drilling bolts in rocks if necessary, while collecting information about the route. This is called completing the first descent of a canyon, and I wanted to discuss what that entails. The experience of physically going into a canyon that no one has explored before is actually the last step of a long process.

The first step is identifying a canyon to explore. This can be done in a number of ways, from hiking around and looking for drainages to studying satellite and LIDAR imagery for a propitious area. Often, we notice a canyon while doing something else and then examine satellite imagery when we get home to learn more about it. Information that must be acquired is the length of the canyon, its topography, the approximate number of rappels and most importantly, the length of the rappels so we can bring adequate ropes for the task. Equally as important, access to the head of the canyon or the technical section must be established, along with an exit point from the canyon and a return route back to the parking spot or a shuttle location. The information gathering phase can be very time-consuming. Available imagery must be examined closely to learn about the topography and approximate length of the drops. Access must be scouted out along with the exit location and often preliminary trips to the top or bottom of the drainage are undertaken to examine the terrain. In some locations a drone can be flown to get better visuals, but this isn’t always possible and isn’t always useful. In short, you want to learn everything you possibly can about a canyon before your first trip into the unknown.

In this particular case, Eric had collected a lot of information. We knew the creek was relatively short, had potentially 2-3 rappels that were most likely shorter than 200 feet, was made of terrible rock and would require a lot of downclimbing or many short rappels down very steep terraced terrain. Eric had scouted the approach and exit, and much of the creek was visible from the trail that intersects the creek at the top and bottom.

The approach hike took about an hour on excellent park trails. We reached a bridge spanning the creek and proceeded to change. We encountered a number of hikers at this point who were wondering what in the world we were doing putting on all kinds of gear and helmets on a cool morning. We did our best to explain canyoning to mostly bewildered looks and wishes of good luck. We entered the creek and proceeded forward gingerly and slowly. It turns out that creeks in Montana are some of the slipperiest terrain I have ever encountered. There is an invisible layer of slime covering all the rocks, so falling is a real hazard. It became apparent that the bedrock was made almost entirely of the sort of delightful weathered limestone that we call laceration rock. This limestone is sharp and will shred any material unlucky enough to come in contact with it. Truly, Siyeh Creek is a remarkable combination of extreme slipperiness and terrible rock. Good times.

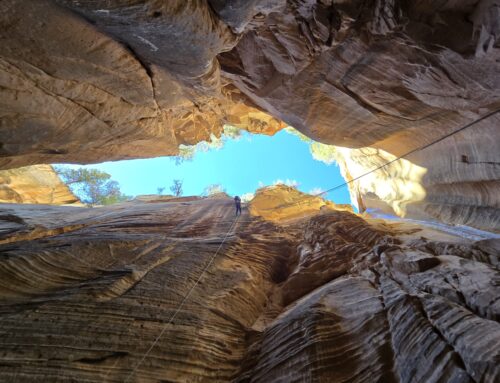

The limestone in this location is weathered in such a way as to form almost perfect steps, descending at least a thousand feet of elevation. Water cascading down these steps forms perfect waterfalls coming down and presents a beautiful scene. We soon reached the technical section, which started with a short rappel down a tall and slippery limestone step and ended on a large ledge overlooking a raging waterfall of at least 200 feet below us. It was apparent to us that we would not be able to descend the watercourse due to the extremely sharp and crumbling rock, swiftwater funneling into a narrow channel, and the inability to see exactly what was below any given anchor point. Of these, the main obstacle was the rock quality: it seemed unlikely we’d find good locations for bolts, while at least one traverse station would be required if not two, and it would be quite risky to go exploring down the watercourse.

After some scouting we determined that the safest option was to rappel on the left side of the canyon, outside the flow. Even there the rock was too crumbly for bolts, so we proceeded to look for natural anchors even though rap lines from the edge of the creek weren’t ideal. Fortunately, there is no shortage of trees in Glacier, and we were able to rig a traverse line to a slippery edge and then do a two-stage rappel from a tree down some very sharp and Death Valley-esque limestone to the bottom of the falls. We had to take precautions to avoid damaging our ropes on the sharp edges and also had to dodge unstable rock shelves as we were making our way down the various ledges.

Once we made it to the bottom, we were able to cross over to the bottom of the big waterfall. It was beautiful and in lower flow could potentially have several good rappel lines… however, none accessible via natural anchors. Now all that remained was about a thousand feet of downclimbing down sharp and slippery limestone steps, with beautiful waterfalls following us the entire way. We painstakingly made our way down the slabs, rappelling where needed. After some final creekwalking, we emerged right on the park trail near the parking lot, startling a couple of visitors. One man in particular kept staring at us with wide eyes. I asked him if he wanted to know what we were doing and he was very interested. So Max pointed to the very top of the waterfall staircase in the distance and told him we had just descended from up there and were the first humans to ever do so. We’re not sure he believed us.

Although it was a very fun day with a great team, Siyeh Creek is at best a two-star canyon, one I would not go back to. There are only a couple rappels down sharp limestone that is actively trying to cut your rope. The downclimb out is very long, slippery and sharp as well. The creek merits the extra star for being very scenic, with sights not easily accessible from the trail. However, this is a good reminder that most first descents do not result in new five-star canyons. The reason we go into the unknown is in the spirit of exploration, to learn about new routes and to pass on that knowledge to others, whether those routes are good or mediocre.