High on the flanks of Mt. St. Helens lies one of Washington state’s most unique canyons. Ape Canyon is located below the Plains of Abraham on the east side of Mt. St. Helens and is adjacent to the Ape Canyon trail. This challenging canyon is an unbelievable combination of Death Valley and PNW canyons, all rolled into one very long day. After having experienced Ape Canyon for myself, I would highly recommend getting some Death Valley experience downclimbing giant boulders and navigating loose scree and dangerous slopes before attempting this canyon. Much to my surprise, my extensive desert canyoneering experience was great preparation for tackling this one. Canyon beta is available here: Ape Canyon – ropewiki. No permits are required, but a Northwest Forest Pass is required to park at the Ape Canyon trailhead.

This adventure was part two of my birthday weekend festivities in September of 2024. We had been wanting to do Ape Canyon for quite a while and it didn’t take much to convince our friend Brian, a Mazamas instructor to join us for his second trip of the season. All the anchors were already set, so it was going to be as easy as it gets, which was definitely not very easy. The trip requires a shuttle, starting at the Ape Canyon trailhead. The drive to the trailhead required us to ford a creek and drive down a rough road. 4-wheel drive and high clearance is recommended. We ended our hike 11 miles later at the Lower Smith Creek trailhead, right after crossing the Muddy River.

We began our approach hike at 5:30am. The hike up Ape Canyon Trail is about 4 miles with 1200 feet of elevation gain. As we hiked this lovely trail I could see giant tree trunks on all sides, but sadly didn’t get to gaze at these magnificent trees in daylight. As dawn broke and we summited and gazed down into Ape Canyon, we saw a red sun rise through smoke above a huge forested valley. After a well-deserved break, we began our descent, which very much reminded me of a Dante’s View canyon in Death Valley: steep slopes and a lot of loose scree.

Ape Canyon has a mysterious past with ties to Bigfoot. In 1924, a group of gold prospectors claimed that they were in the wilderness when they were attacked by 7-foot tall ape-like creatures who pelted them with boulders. One of the creatures was shot three times and fell off a cliff into an inaccessible canyon, henceforward called Ape Canyon. Although this story was investigated by US Forest Service rangers and debunked, the myth persisted.

Another incident from 1950 concerns a man named Jim or Joe Carter who was with a large climbing party and separated from them to take photos of the group near Ape Canyon. Accounts of what happened after he took the photos diverge. One account says he was skiing in a great panic and taking a lot of risks as if being pursued before being chased into Ape Canyon. Another account states that he turned off into the wilderness by Ape Canyon. Many people spent five days searching the canyon, but no trace was ever found.

Although we sadly found no signs of Sasquatch, there were definite signs of a bad snowmobile accident in the canyon. As soon as we scrambled down to the first rappel, there were signs of a SAR operation consisting of a rebar anchor tied to the thickest rope I’ve ever seen and a completely wrecked snowmobile at the bottom. We photographed the wreckage and continued onward and downward.

Ape Canyon is a giant crack in the earth, descending several thousand feet in elevation. The canyon was scoured by lahars (volcanic mud flows) in 1980 during the volcanic eruption. Structurally, it is extremely unstable with rockfalls and rockslides changing the character of the upper section each year. One of the rappels that had been rigged on a giant boulder last year is now very difficult to access because the block slid downhill about 15 feet and now needs a stiff downclimb to access.

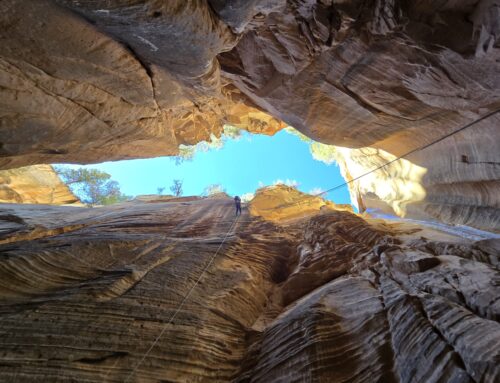

The canyon can be divided into three sections. The upper section is a dry gorge that plunges straight down with a lot of downclimbs, scree and six short but awkward rappels. The most interesting rappel in this section is called the Bolt Hole rappel, described above, which has a single bolt on a boulder in the canyon and requires rappelling through a rabbit hole under huge chockstones wedged between the canyon walls. The boulder has slid down and now requires a meat anchor or tricky downclimb to access. This part of the canyon is quite intimidating with narrow and tall canyon walls, no vegetation, giant boulders scattered throughout and giant chockstones overhead. Quite an amazing sight in Washington.

Once you approach the middle part of the canyon, you can almost believe that you’re still in the PNW. Water starts to trickle from springs and pools and waterfalls appear. Plants begin to emerge from seeps in the walls. It was time to put on our thin wetsuits and rain jackets! Shortly after we entered this section, the walls narrowed and we found ourselves at the top of a 100-foot waterfall, which was a beautiful rappel in the flow, hemmed in by canyon walls on both sides.

After this point, the canyon becomes more technical with rappels coming one after the other. There are eight rappels in this section. Although the rappels are all short, they are extremely awkward with many off chock stones down incredibly slippery chutes. The algal growth on the rocks makes it impossible to keep your feet under you and we wound up rappelling on our knees or sides most of the time.

Eventually we reached the confluence with another fork of the canyon. Brian was very interested in learning more about this fork, which has not been descended yet, and he brought his drone to get footage. We took this opportunity to have lunch and relax a little bit before entering the lower and final section of the canyon.

The lower section is the most beautiful, with polished bedrock of many different colors, more flowing water and deeper pools. There are six rappels in this section. Of particular note is a lovely section with polished pink/purple bedrock on one side, an incised channel of water in the middle and gray rock on the other side, just inches from each other. The last rappel is very pretty, descending next to a scenic little waterfall and into a deep pool. Framed by smooth, tall walls, this chamber is a lovely end to an amazing canyon.

A short time later, we exited the canyon and found our way to a large expanse of rock to change into hiking clothes and gaze at the immensity of the canyon we just descended, thousands of feet above us. Now, it was time for the bushwhack to begin. I think for me, the exit out was the hardest part of the whole day. Ape Canyon comes out near Smith Creek but requires about 1.5 miles of bushwhacking and creek walking to get to the Smith Creek Trail. There are some areas of dense forest to get through, but the presence of game trails is very helpful. Once on the trail, it’s about a three-mile hike on this well-maintained trail to get to the Muddy River. Not far from the river, my eyes spied something orange in the moss layer on the ground, and sure enough! It was a large and delicious looking lobster mushroom. And next to it was our friend the bolete that we found exiting from Big Creek the day before. As we had a long drive ahead of us and there wasn’t any room in my pack, I gave these treasures to Brian to take home.

We arrived at our car shuttle exactly 12 hours after we started, and I was pooped! We did 11 long and difficult miles that day and got to see a special place that maybe fewer than 25 people have descended from top to bottom. Ape Canyon was one of the highlights of my summer, and together with Big Creek, made for one of most amazing birthday weekends I’ve ever had.